Key

The following keys are used throughout this dissertation;

[1]…Page number (now not used)

(1) and 1…Illustration number.

(1)…Quotation source number (all listed under source).

(1)…Bibliography number.

[1]…Film credit number.

Contents

DEATH. 6

Beforec.1400: The Origins of Death, Personified. 9

1400-1499: The Beginnings of Decomposition, and the Rise of the Reaper. 16

1500-1599: The Time of the Hourglass. 23

1600-1699: Death, Time, and Wings. 28

1700-1799: Death and Destruction. 32

1800-1899: A Period of Overt Sentimentality, and the Decay of Death. 37

1900-1995: The Resurrection and Commercialisation of Death. 42

GRIM REAPER. 50

Photograph and Illustration Credits 51

Sources. 61

Film and Television Credits 65

Bibliography 66

Churches visited. 75

Figures

Figure 1: Various Tarot cards 8

Figure 2: Roman moasic 9

Figure 3: Celing Boss, the Four Horsemen, 1340-1410 13

Figure 4: Ceiling Boss, Death followed by Hell, 1340-1410 13

Figure 5: Illustration from Boccaccio's Decameron, 14th c. 13

Figure 6: Three Living and Three Dead, early 14th c. 15

Say the words 'Grim Reaper' or 'Death,' and an instant mental picture is formed of a tall, male skeleton dressed in long, black robes, swinging a scythe and holding an hourglass, while possibly playing chess with a mortal, for their life, a figure referred to as 'Medieval.'

The idea of a 'Death' has, for a long time fascinated me, but I never imagined that this typecasting hides the true complexity of the development of Death in European culture. During this dissertation I will trace Death's evolution in form and personality, and compare 'his' progression with man's changing attitudes. This will be mainly explored through the 'arts,' concentrating on funerary, both sculptural and relief, 'fine art,' which is mainly painting, and lastly literature. The history will be traced century by century beginning with a general section on 'Before 1400,' the period where Death starts to emerge from early vague sources as a separate entity from God and the Devil.

I will also examine other figures that appear in this mythological niche, figures that have helped dictate his appearance and behavioural patterns and include Father Time and Sleep. Sleep is an enigmatic figure that never appears, in painting or sculpture, but whose relationship to Death is always made clear in literature.

During the research of this dissertation I became aware of the world wide appeal of Death as a personified 'corpse' (skeletal or otherwise). These cultures often have differing attitudes towards Death, sometimes creating complex Gods that rule the various 'underworlds,' other times using sex, or creating a more humanistic figure. The European Death has also followed some of these paths through the various mediums, and I am aware of their possible influence, but have had to restrict my view. Having said that, I have included some from American culture, especially in the twentieth century. This is because of the American domination of the one greatest 'cultural' phenomenon ever, film.

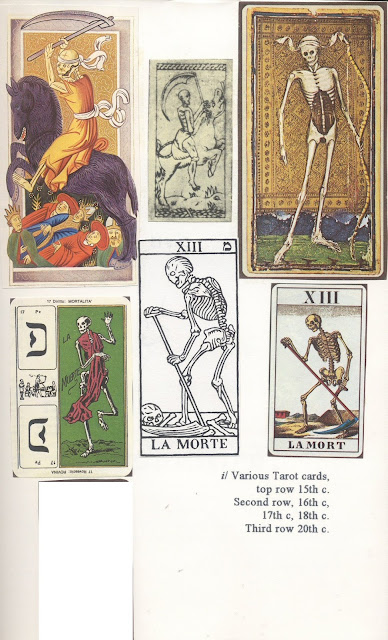

Death also appears in the notorious Tarot (i), on card number thirteen. The pattern created can be compared to the main dissertation, especially in form and symbolic usage. The meaning Death in the Tarot is not in the literal sense, but in a symbolic one, the dying of an attitude, for example, and the rebirth of another. It is only certain circumstances that Death predicts a death.

Please note that I will refer to Death as 'Death,' as the term 'Grim Reaper' is a modern term that I have been unable to pin down to its origins, and it leads to certain assumptions as noted at the start. Also, for reasons made clear in chapter 1, Before 1400, I will refer to Death as a He, unless the situation dictates otherwise.

Figure 1: Various Tarot cards

Top row: 15th C.

Second row: 16th C., 17th C., 18th C.

Third row: 20th C.

Figure 2: Roman moasic

Before c.1400: The Origins of Death, Personified.

Skeletons as personifications of death start appearing early in culture, Egyptians used them to decorate feasts, the idea to promote friendship and deter wickedness, with reminders of death. The Egyptians developed the symbol of eternity often associated with Death, a snake holding its tail in its mouth. This will also be twisted to be more associated with decay, and the first sin.

The Greeks were the true creators of Death, however, with their complex God and Goddesses, but it is Father time who contributes the most to Death. Their image of 'Time' was simple, until the Greeks themselves mistook their own word for time, Chronos with an outdated God, Cronus, a God of agriculture, the symbol of who was a sickle, becoming later the scythe of Father time. Time was only given the snake by mythographers of late antiquity, other attributes came later. (2)

The Romans in particular used the form of a skeleton, to create a warning, introducing them to banquets, cavorting skeletal figures on cups (referred to as larvae), and presented to the revellers in the form of miniature jointed skeletons, again an aid to promote enjoyment with the reminder of death. These were occasionally joined with messages such as: edite! bibite! post mortem nulla voluptas! ("The Hunt, the baths, games and pleasure-that is life.") (3) Or "Know your self and your mortality". These often adorned mosaics and tombs, grim messages to the general populace to enjoy life while living it. (1, chapter title page) Pompeian dining-rooms also contained the message of death with skulls carved directly into the stone fabric of the building, a common practice long before the explosion of Mount Etna. These small appearances of 'death' will both be continued to be used, and contribute to Death's evolution in personality and form.

The Romans also used a more familiar and defined form for Death, as Horace, a poet makes clear;

Pallida Mors aquo pulsat pede pauperum tabernas Regumque turris.

Pale Death breaks into the cottages of the poor as into the castles of kings.

(4)

This contains an interesting set-up for the Revelation of St John, the Apocalypse, (thought to of been written about c. 80-90 AD).

"And I looked, and behold a pale horse, and his name that sat apon him was Death and Hell followed with him

And power was given unto them to kill with sword, and with hunger, and with death, and with the beasts of the earth. "

(5)

Which could be defined as a variation on a 'Pale Death.' Death in this context has no defined form, interpreted in many different ways to what was probably what was intended. 2 illustrates the four horsemen, 3 another part that causes confusion, Death and the reference to 'Hell', translations ranging from, Hell riding on Death's horse, or Hell as a fifth horseman, or even running behind as a great beast. Horace again sums up this idea well;

Post equitem sedet atra Cura.

Black Care sits behind the horseman.

(6)

Other mentions of Death in the Bible, are mainly about the destruction of Death by God in the last days of earth;

The last enemy that shall be destroyed is death.

(7)

And in these days shall men seek death, and shall not find it;

and shall desire to die, and death shall flee from them

(8)

and appears to be any adversary to God, an evil figure, often associated with Hell and the Devil;

We have made a covenant with death, and with hell are we at agreement.

(9)

Although in some cases Death seems to be helping God, and can be seen as a replacement to an angel at a death. (4)

Quote 8 does bring up another important question, that of the sex of Death. Death is normally seen as a 'he', possibly because females are always the mother nature types, who create and heal, tend to the 'home fires' whereas men destroy, fighting wars. There are rare examples of Death as a 'she,' but these tend to be isolated examples until much later.

However, it is only around the fourteenth century that the figure of Death really starts to appear. These figures are mainly manifestations from two sources, from the thirteenth century, two themes that were to echo down time in one form or another. These 'Death's' are barely recognisable to modern preconceptions.

The first has eastern roots, and is described as "The Meeting of the Three Dead and the Three Living," or simply "Trois Morts" (Three Dead.). It is based apon a late thirteenth century poem, Le Dit des trois morts et des trois vifs. (10) The story has many versions, the general idea that three princes return carefree from hunting in the forest. They meet on the way three dead who accost the princes, telling them, "Sum quod eris, quod es olim fui." "That which you are, we were; that which we are, you will be." (11)

This then becomes not merely a tale, but one with a strong message, they are more often found in churches so take on an admonitory tone. There are other interpretations, with the figures more recumbent. In one rendition it is three kings, who come across three open coffins, a hermit tells them that the bodies are themselves, a far more direct and chilling warning, though occasionally the dead attack the living. It is interesting that in many cases the victims are young, or rich (or both), a reminder to all that youth does not mean immortality, riches cannot buy off death.

The theme is shown even more clearly with the "Dance Macabre", often confused with "The Dance of Death." Dance Macabre, Protestant in origin, illustrates the idea that we are all equal in death, and is often portrayed as a long line of people stood beside a skeletal or partly decomposed figures of death. The line starts with the most important, ending with the least, for example.

Pope, Emperor, cardinals and lesser ecclesiastics, throughout the various ages and occupations and ending with the peasant. The order often depends on the religious beliefs at the time, as well as other factors of culture and what the artist and populous would instantly recognise.

Of course, despite the 'impartiality', there is still a defined order of hierarchy to the grave. It was performed as a dance for pleasure in the fourteenth century, as well as in religious drama. The 'Dance Macabre' and 'The Three Living and the Three Dead' are superficially similar, the rich and mighty are reminded of Death, and that it is not just restricted to the poor.

The Dance of Death, is very different. This was a medieval belief that the dead rose from their graves to perform a dance in the graveyard, before setting off to claim the living for an early grave, only a passing similarity to the single figure of Death, but important as it sets certain perceptions as to Death, the most important being night and darkness. Although some do carry scythes, and are occasionally robed, these figures are rare before the fourteenth century, and do not appear in any type of funerary. All of these images were designed for the illiterate masses, as visual aids, to teach, and remind.

Funerary art of this period was rather basic. The majority of stones are carved with a name, date, message, and perhaps the occasional cross or other religious imagery. About the twelfth century figures started to appear, effigies of the person, that looked 'alive.' These are often recumbent figures, a term that is applied to a type of figure that are carved as if they are standing, their robes hanging down despite the fact that they are lying down. These would expand into more sophisticated versions, as man's confidence and aptitude for creating grew, so did his imagination.

Funerary art of this period underwent massive changes. As man's Cathedrals rose to meet God, and the churches' power and wealth grew, so did the monuments of the ecclesiasticals' and rich. They reflect medieval mans obsession with decay and death, and his growing awareness of his own mortality. This was a time or violent death, with disease, war, famine taking lives that were already shortened by ordinary life. The potency of the vicious, gruesome images of Hell lessened, and Death was used to promote fear of death.

Death is not only shown as a skeleton, as modern eyes would recognise him, but a cadaver, often with wounds to the abdomen. 6 (chapter title page) is an example of funerary, ( a 'Transi' figure, not Death but merely a reminder of what waits for the body beyond the grave) 7 is an early poison bottle label, warning vividly of the contents with Death. These reveal much of mans knowledge of anatomy at the time, a knowledge still in its infancy. Sexual organs are rarely seen, and tend to be hidden under winding cloth (used in burials) or hands. This excludes breasts, which appear on both the living and dead, (8) the idea of Death being to frighten, not titillate.

Vanity is warned against in 8, the beautiful young woman is overshadowed by Death, who warns that her beauty will not last with the hourglass. 9 contains the figure of Pride, with her companions, lechery, gluttony, anger, envy, sloth, avarice, the seven deadly sins.

Death stabs her with a lance. In direct contrast, Death flirts with women in 'La grant dance macabre des femmes' (10), adding a new dimension to Death, who has been portrayed as either a clown, or a sinister figure that comes calmly to take away the dead.

Wings are also occasionally illustrated, 11 has leathery wings, relating him closer to the Devil, than the softer winged Angels. (12) Death does carry the more familiar scythe (11), but he arrow is just as common at this stage (13), as the plague was originally thought to of been carried by arrows. Death also occasionally carries coffins, but the image died out about 1500. (13)

The Great Plague was now in full force, claming approximately twenty-five million lives. 'Dance Macabre' became ever-more popular. Traditional versions (14 to 17) still ran from the highest to the lowest, 17 including an infant protesting the pull of Death. 10 and 18 are examples of the more fractured style, the figures are portrayed separately or as a pair in a series of illustrations, often in less fanciful situations. Death comes to the victims at, work, (18) worship (19), home (20), with neither man nor woman safe any where.

This then became Artes Moriendi, the English version of a Book of the Dead. "Death and the Miser" by Bosch (20) illustrates part of one. These were intended to give the person self control after death by guiding them through the process of death, and became popular during the plauge. These tend to be varied, but a common version is divided into three chapters, the first describing how 'all' races are taken to death, the second, 'Transi' figures are seen with other forms

of 'death', and lastly, Death appears. Death was also a central figure in the medieval morality-play, Everyman, that was very popular in its era.

Some of the most striking images of Death has originated from St John's Apocalypse, the most famous being Durer's The Four Horsemen, (21) though others do exist in large quantities (22). In both, Death is chased by a bestial Hell, the two being identical, but Death is interpreted differently. Durer's Death is an old, frail man, the other a corpse wielding both sword and scythe. Retribution and Death are often linked, van Eyck's Last Judgement (23), for example. Here Death presides over many deaths at once, an image more associated with Heaven and Hell where man is judged en-mass, instead of individually. This is further emphasised in 24, where an army of Death attacks the living, both analogies of the plague that devastated the population indiscriminately.

The Triumph of Death became a popular theme for painters at this time. One version (25) by Palerma, is based on the series of six poems entitled, 'Tronfi,' by Petrach from the first-half of the fifteenth century, Death occurs in the third poem in the series, in which each poem 'Triumphs' over the last, the sequence being, Love, Chastity, Death, Fame, Time, and lastly Eternity. These poems would inspire painters, and the Triumph would appear in many forms, 26 where Death rides on an ox cart, people die around him, (Oxen were often used for heavy labour in much of Europe, and would be an obvious choice for continental artists who would be used to the sight.)

This is all linked to mans attachment to life, and the lengths he would go to preserve it, especially during the virulent plague. Combined with an average life span being less than forty, medieval man had a definite fear of Death, and the consequences after. The Church therefore strove to reminded man constantly of his plight and the horrors involved, to keep him from straying. However, it did also have a detrimental effect, spawning the 'live now, die later' philosophy that became so common in the age. 'Dance Macabre' would be a common tool, but with the advent of books both Dance

Macabre and the Dance of Death would merge. Even today well-known encyclopaedias such as the Encyclopaedia Britannica, tend to merge the themes. The Dance of Death was still illustrated occasionally, such as the 'Orchestra of the Dead' (27).

The Three Living and Three Dead is also pictorially represented, with many variations, 27 to 31 both show different versions. In 27, the hermit shows the kings the three corpses, which are in the three stages of decomposition, gaseous stage, as the body bloats with the rotting of the internal organs and food still in the stomach, mummification, then skeletal remains, a definitive reminder of the horrors of death. 29-31 is a slightly more traditional form where the dead stop the living, who have been hunting and womanising (a woman can just be seen at the end) in the road. It is interesting that the figures of Death were once skeletons, but retouched and only given bodies in about 1904. (12)

As well 6, there are many examples of funerary containing the image of a decomposing corpse, echoing Death, but not being Death. These indicate strongly the passing trends of the appearance of Death. The appearance at this point tended more towards skin stretched to breaking point across the body (32-33), often with surprising variety. The print (34) by Bellini, is a unique design with the monks below the corpse (it also provides an exception, the corpse's genitals are showing, adding to the gruesome reality of the piece) a similar piece (35), a 'memento mori' (translation; remember to die) uses the inscription "Once I was that which you are and what I am you will also be." More reminders that death will strip away earthly vanities and possessions, and a reminder of the fate beyond.

Perhaps the most surprising thing about Death is that he exists at all. Before, judgement was thought to of been delivered by God, at judgement day, and not before, the whole of mankind judged 'en-mass'. The appearance of Death visiting each person individually shows a strong cultural change, man is now seen as an individual, rather than a mass of 'humanity'. This is emphasised by an illumination (36) of God giving Death three arrows, and a list of names, those to die that day. These images are very rare, the connection is never really made between God and Death, they remain separate entities doing the same job. There is a possibility that Death was not seen as the judge and jury, rather as a carrier, guiding the souls to the grave, and final judgement at the hands of God and St Michael, as the Apocalypse according to St. John dictates. To this day, Death is rarely twinned with God, the Devil is a more familiar companion.

1500-1599: The Time of the Hourglass.

In the sixteenth century, man's curiosity was directed towards himself, autopsies and anatomy classes giving doctors an insight into how man worked, and becoming a vivid spectacle for the masses and the rich alike (38). Anatomical pictures often had the subject posed, as if in life. (39) To modern tastes, this would seem morbid, but post-medieval man was used to the sight and smell of death to a greater degree than today. Momento Mori images also started to be included in objects such as jewellery, as in the Tor Abbey Jewel. (37, chapter title page.)

Death's image appears to be stuck in this era, with the hourglass (40). The cumbersome sundials were replaced by hourglasses, becoming common after c. 1500. Man became aware of time in ways he hadn't been before, measuring his life in grains of sand. Modern Death carries an hour-glass, simply because watches and clocks were expensive, huge, unreliable and rare, and Death was aimed more as a warning to the poorer communities. Death also gained a specific term, sardonic, which comes from saradine, a type of root that..."Those who die from having eaten it look like a person laughing" (13). Death's personality started to emerge, with the posing becoming more vibrant (41).

The 'cleaning up' to a more skeletal Death now started. 41-53 reveal a duality in the personification, the now traditional clinical skeleton apposed to the decomposing version. These also include many objects associated with Death, skull and cross bones, often a warning of danger and death, snakes, the symbol of eternity and evil, hourglasses (often winged), indicating the fleetingness of time, shovels, that indicate both the grave and a lifetime of hard work, as well as scythes, shrouded bodies, arrows, coffins and crowns. These are used effectively in 42, a plague scene framed by both Death (holding the flaming arrow) and Time, two figures that also appear in 43-46, with a cherub-like figure indicating re-birth. It also includes an interesting montage of the scales of justice, winged hourglass and skull (46). 47-51 again reveals the underlying trend, the maggot eaten corpse, (47), with 48 and 49 showing the direct contrast between death and life in a single monument. Originally both of the figures were surrounded by murals of day and night, night for the corpse again indicating the connections of death and black.

These are examples of a passive Death, not taking direct action against any one person, whereas in 50 Death appears able to break off life at any point he pleases, as he stands dominating the wheel of life, those on the wheel totally at his mercy. Heaven appears above him, ready to welcome the worthy. In direct contrast to this, Death is paired with the Devil (the goat) taunting the knight (Christianity) (51). This again raises questions of Death's allegiance, which is made unclear by the feathery wings of 50 and 52, and the way God abandons man to Death, in Genesis iii, 23. (53)

53 comes from Holbein's 'Dance of Death' that was originally titled "Images and illustrated facets of death, as elegantly depicted as they are artfully conceived." This is the more accurate title, as it is not a Dance of Death, but a Dance Macabre, as Holbein's version is set at all times, in many situations, an excellent example of how the two themes became confused. Death is seen first at the Expulsion of Adam and Eve;

"So God drove man from Paradise,

By daily toil to win his bread,

And Death came forth to claim his prize,

And number all men with the dead."

(53).

The 'Dance' continues until the end, where judgement excludes Death. The scenes vary, and include Death in many guises (54 and

56), including a rare appearance of a female Death, witnessing the possible fall of a nun (56). He is sometimes accompanied by other skeletal figures (57), and he often holds props including skulls, and dresses up to illustrate his point. The hourglass is a popular object, it is on its side in 54 so the sand, and therefore life can no longer run, the same to be said of the broken version in 57. Death shows it to victims, has it hung around his neck though usually the hourglass stands on it's own, hidden within the detailed pictures. Death is given a range of 'emotions,' from happy (57), to cruel (54), creating both a response and indifference in the victims, (55 and 57). He takes all unexpectedly, quickly, or at his leisure. At the end, two skeletal hands hold a rock above the hourglass of life, ready to destroy it. (58)

'The Triumph of Death' by Pieter Bruegel the Elder (59), is similar to an earlier picture, (24), as the greatest to the lowest are attacked by the huge army of Death, the apocalypse without judgement, and with few beasts from Hell. This picture is too vast to describe in a few words, but examined minutely many similarities can be seen with Holbein's Dance of Death. However there are unique and important details to be found, the army using coffin lids as shields, Death on a red horse (more associated with War from the apocalypse), and both winding cloths and normal clothes are used to dress Death, often echoing the people they attack.

The 'blending' of the two themes together, and the subsequent loss of 'The three living and the three Dead' means that many appearances of Death have no clear origins. 'Death and the Gallant' is a new theme that probably came from 'The Three living and Three Dead,' (60) taking the idea of a man meeting Death, and his reaction. The Gallant appears to be trying to 'buy off' Death, who offers him a cut rose, symbolic of a life cut off at its prime.

Death is now becoming less impartial, and more involved with the 'lives' of his victims. He can be seen directly interfering with their lives in ways that have little to do with death, and mocking them. Again, Death has no real allegiance to God or the Devil, but capable of action of his own, though these actions can be interpreted as 'evil,' frequently contrasted with 'good'. For example, in 61 a knight carries his lady love away from Death. Death and sex appear more frequently, becoming more vivid. 62 is an excellent example with a lecherous Death groping a girl, while forcing a kiss. 63 has a young woman, bare-breasted staring at the viewer as Death leers over her shoulder, her beauty off-set by both Death and the hideous baby/foetus clinging to her, it's future uncertain. William Shakespeare often used the idea of Death and sex (or even love) in his plays:

Shall I believe

That insubstantial Death is Amorous,

And that the lean abhorred monster keeps

Thee here in dark to be his paramour?

(14)

The skull was used a great deal at this time especially in funerary. 64 is an entrance to a 'Plagueyard,' warning even the illiterate that danger lurks within (a warning valid even now as the plague can remain on dead tissue for centuries). Holbien's "The Ambassadors" is a famous use of the skull in portraiture, (65 and 66) with the distorted skull only visible from one angle, the message rather lost in the technical skill needed to execute it. A more vivid reminder of the skull's message can be seen in 67. The aged couple stare mournfully out at the viewer, the mirror reveals the truth of the painting, instead of the visages of the couple, two skulls appear. 68 has a skull on an hourglass, holding a thigh bone in its mouth, 69, a commemorative marriage painting, the couple stand either side of a corpse, hands on a skull with the motto;

'The WORDE OF GOD HATHE KNIT VS TWAYNE AND DEATH SHALL VS DEVIDE.'

(69)

The skull therefore becoming a reminder of the corruption of the flesh, the corpse sealing the image. It was also used as a 'miniature' Death, used where money or space didn't allow for extravagance, or used with the image of Death. 70 is one of the more unusual uses for a skull, that also reveals the common place use of this images, it is incorporated into a printers mark, complete with hourglass and snakes.

1600-1699: Death, Time, and Wings.

Merely, thou art death's fool;

For him thou labour'st by thy flight to shun,

And yet runs't toward him still.

(15)

As Death's personality changes, so do the size and complexity of the designs of monuments. Time becomes ever more popular, and linked strongly with Death (92), the hourglass is now clearly associated with Death, 71 (chapter title page) creating the ultimate logo for Death.

There's an experienced rebel, Time,

And his squadrons Poverty;

There's Age that brings along with him

A terrible artillery:

And if against all these thou keep'st thy crown,

Thu'surper Death will make thee lay it down.

(16)

Skulls experienced an increase in usage, that varied from spoons, (72) to memorials, and paintings (82). 72-76 show a plainer use of the skull, 73, the entrance to a graveyard. (This was referred to by Charles Dickens in his book, "The Uncommercial Traveller" as 'St. Ghastl Grim.') They are also frequently hidden in monuments, (74-75) as man's obsession with Death occasionally showed restraint.

There were more elaborate uses of skulls, however, 76, 77 and 78 reflect an Italian idea of a Charnel House, where the remains are left on display to the public. Both have the various bones showing, hip, hands, thigh and so on. Wings also are more common, frequently used on 'Death's Heads' (79 and 85), it is noteworthy that both are feathered, and that the scenes depicted are religious in nature, the appearance of leathery wings might upset the 'purity' of the design, with suggestions of Hell, and damnation.

A slightly more sophisticated appearance of the skull is employed in 'family' memorials (80 and 81). Monuments were created when a parent died, which includes all of their children, size dictating age. The family members that died before the monument was built hold a skull in their hands. 81 is a stillborn or baby death, the swaddled child leans against a seemingly giant skull.

Even these seemingly placid skulls did occasionally revel a personality at times, from the subtle 82, to the direct, the eyes of 83 and 84 mesmerise even from a photograph, and the scream of triumph from 85 can almost be heard.

The 'recumbent' figure was quickly becoming more active. Despite the originality of 86 as a gravestone, traditional recumbent figures, seem like just beautiful anatomical studies (87 and 88). 89 is a twist on the idea, a wall mounted monument, the skeleton stands upright, holding a cloth. Again, it is not Death but a new form of demi-skeleton, which is only partially revealed. 90 is possibly a better example, the skeleton leans out at the viewer with the straightforward stare of an inquisitive child, whereas 91 is an unhappy marriage of a demi-skeleton and Death, the robed figure sits behind bars, the human face up above in a portrait.

A slightly more sober version of Death can be seen in 92, along with Time. This is in complete contrast to 93, where Death comes charging out from beneath the monument to claim his prize, holding an hourglass, and wielding a scythe. This sort of image is reflected in 94, Death interrupts a card game and people react with fear, but Death appears quite jovial in the task. Death also takes on a more human and humorous aspect as he reveals the dangers of smoking in 95.

Even paradise contained Death, the phrase, 'Et in Arcadia ego,' coined in 17th century Italy was used in paintings. The phrase, meaning-"Even in Arcadia I (i.e. Death) am to be found" warned that even Arcady was not immune to Death, so reminding the viewer of their mortality (17). Sleep is still considered to be related to death, in Macbeth, Shakespeare was very clear on the point, as were other authors at the time.

Shake off this downy sleep, death's counterfeit,

And look on death itself! up, up, and see

The great doom's image!

(18)

Half our days we pass in the shadow of the earth;

and the brother of death exacteth a third part of our lives.

(19)

Anatomy lectures were becoming more elitist, and less for the public as it strived to forget death, they saw too much of it close up. Portraits were still popular, though notice how clean the body is, there are no fluids or grotesque details (96). The same could be said for the corpse in 97, also note the anatomical skeletons dotted around the room, many are posed including a rider and horse. This 'cleaner' Death is shown no where better than in 98, the young woman goes from life to skeleton with no intermediary stage! Note also the snake as part of her collarbone.

Portraiture still used Death within the composition, 99 is a wonderful example of a royal commemorative portrait with Death. It is extremely similar in composition to 64, as Death grins over Queen

Elizabeth the First's shoulder while two cherubs presumably guarantee a place in heaven. However, Death was seen less, with skulls becoming more prominent in portraiture, the sitter 'pondering his own mortality' with a skull (100). This was gradually watered down into 'vanitas' painting's, reflecting on the fleetingness of life without a person, but with objects such as hourglasses, cut flowers, skulls, bubbles and other objects associated with cessation of time, and fragility of life (101).

The best use of the skull is to advertise a funeral business. 102 is thought to be the first ever commercial "coffinsmaker" that did everything, before funerals were less organised, and no-one supplied, "all other Conveniencies Belonging To Funerals."

1700-1799: Death and Destruction

"Who can run the race with Death?"

(20)

Until now, the 'traditional' hooded clock has been missing from our image of the traditional Death. The eighteenth century saw the beginnings of this necessary part of our preconceptions of Death, but even at this late stage it is still used sparingly, shreds of cloth are far more commonplace (103, chapter title page). The only true example in funerary I could find was in Lady Nightingales monument in Westminster Abbey (104 and 105), there are examples in funerary invitations that I will examine later.

Death suddenly gain's life and stature in the various mediums not seen before, again in 104 and 105 Death lunges towards Lady Nightingale with an arrow, her husband desperately tries to ward off Death. As society became more moralising, so biblical paintings became ever-popular. The rewards of sin are graphically illustrated in 103 (chapter title page) as she fights off both Satan and Death, again full of vigour (and enthusiasm).

Sentiment also invaded Death's Realm, from violent images such as 106 and the direct message of Death in 107, 108 appears to tenderly convey the soul to Heaven. This can also be the interpretation of 109, Death is not threatening as he gently advances

towards the old man, his arms wide open, pointing the arrow inwards and not towards his victim. Goya's 'Jusqu'a la Mort' (110) uses an old woman to portray Death, with a hint of a skeletal face betraying the homely appearance of the picture. 111 includes a skeletal man and wife clutching each other in Death, the woman's hands clasped in prayer. Even inscriptions carried on this emotional outlook;

[22]

Era sin could blight or sorrow fade,

Death came with friendly care:

The opening bud to Heaven conveyed

And bade it blossom there.

(21)

Perhaps the most original, and intricate appearance of Death is 112. Everything in the photograph is made from human bones, and decorate an entire crypt. The robes are monastery, though many of the other clichés can be found such as winged hourglasses, scythes.

The destruction of Death, and time became a fairly popular subject for both art and sculpture, a Hogarth sketch has Death fighting with George Taylor, in the first, Death is winning the encounter (113), Taylor fights back in the second, breaking Death's ribs (114). In 115 and 116, Death is dramatically trampled by a life-sized angel, also in a similar tone, by the risen Christ at the Apocalypse (117 and 118), Death's crown of domination falls from his head. Death is again defeated in 119 (detail 120), by Time against a back drop of a falling pyramid, an ancient symbol of time dating from predictably, the ancient Egyptians.

121 has Death responding to the call of the apocalypse, hourglass at side, again the apocalypse is illustrated (122), Death tramples the masses on a horse, horror brought into the picture with the strange mix of flesh and bone, it is noticeable that flesh is only used when a 'shock' value is expected of the viewer.

Death's Heads were still popular, and now go some way to resolving the problem of the wings. Death is given leathery wings in

123, and has with him an hourglass, on its side, emphasising death, with what must have been an arrow. This is counterbalanced by an angel's head on the top complete with feathery wings. This conjures up images of Heaven up, Hell down, further emphasising the idea of leathery wings equalling evil. A gap-toothed grinning Death (124), given a to emphasise an evil countenance reinforces this theory, although it is likely that there are examples that do not fit this

[23]

hypothesis. Perhaps the most interesting version is 125, which have both feathered and leathery wings. It has been suggested that the skull is turning from Death to life, indicating resurrection. I think it is more likely to be life to death, as the skull would turn from left to right, the way the English language is written, or indicating the person has gone to Heaven, turning their back on Hell and all that it entails.

Tiny 'memento mori's' shaped as coffins made a brief appearance, 126 contains a tiny skeleton, and 127 includes an hourglass within the design. (A 'snuff' box.) Masonic circles also used forms of 'Death' in rituals, and decorative pieces, each with their own 'meaning.'(128-129)

As the undertaking business developed, so did the size and complexity of the funerals, and the introduction of official invitations often designed for the particular funeral. These started off being medieval in style, though with intricate detail. 130 is the epitome of these invitations, including many images, even the funeral up to the burial. Memento Mori (as well as a translation), Death (with arrow) mirrored by Time who holds his scythe and hourglass, winged skulls, hourglasses, angels and skull and cross-bones fill every space, even the gaps in the 'Y' are filled. The occasion is not sad, rather the celebration of a life. 131 is less joyous. Death dominates the top, shown as a 'king,' and again he carries an arrow. 132 has the first direct relating of Death to clocks, despite the fact they have existed for two centuries already. The fire on the skulls indicates the eternal flame.

Then it all changes. 133, from 1720, is a far more formal version.

Set in a church, Time is gone and Death is shown with winged hourglass and scythe. The whole scene is filled with weeping cherubs, the funeral procession is suitably grim. 134 is a step back, but is still filled with grim messages, 'Death is Sins Wages,' and the bizarre 'Die Dayley...To Live Eternally,' referring either to sleep, or that we are all slowly dying from the second we are born.

135 includes a lethargic robed Death desperately clinging onto the burial wrapping of the subject. In a surprisingly morbid ticket, the dead man tries to chase after Time, just as Death claims him, another warning about the squandering of time. 136 contains the strangest Death of all, a skull appears from in a robe, it is clearly inhuman. Despite the obvious skeletal figure, the hand is fleshy and deformed as are the feet. Political cartoonists also took up the image of Death, (138) something that has continued to current times.

The new aspect of Death just starting to emerge, compassion, would destroy the 'uncaring to the point of cruelty' personality of Death, and as the monuments became more sentimental, it would almost kill Death himself. This would gain momentum in funerary in the next century.

1800-1899: A Period of Overt Sentimentality, and the Decay of Death.

And come he slow, or come he fast,

It is but Death who comes at Last.

(22)

For a time renowned, especially in Victorian England, for its devotion to death, mourning, and all the paraphernalia to go with it, the nineteenth century is devoid of Death. 138 (chapter title page) typifies a now clichéd appearance of Death. Death's use in religious teaching is worse, (139) the priest pointing from Heaven to Hell, Death, checking the hourglass, the mourners cry dramatically. The scene is orchestrated for maximum impact, but lacks to power of medieval images, becoming a shallow copy transparent in its motives. There were, however, some vivid words written with Death on the subject of war.

The angel of death has been abroad throughout the land; you may almost hear the beating of his wings.

(23)

Half a league, half a league,

Half a league onward,

All in the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred.

(24)

Into the jaws of Death,

Into the mouth of Hell.

(25)

Despite this, Death is reduced in stature even more, as Archady is also overwhelmed by sentiment, The words now seem to imply an epitaph on the person, perhaps a shepherdess who lies entombed, 'I too once lived in Archady' missing the original meaning so that eventually Archady simply becomes nostalgia for a lost golden age, or for the passing of youthful love, not as a warning (26). Again many of the sentiments of the time echo this loss of power, the watering down of Death to a mere shadow, yet also keeping much of the dignity afforded Death that in the next century will be all but lost;

"To that high Capital, where kingly Death

Keeps his pale court in beauty and decay..."

(27)

"How wonderful is Death,

Death and his brother Sleep!

One pale as yonder wan and horned moon,

With lips of lurid blue,

The other glowing like the vital morn,

When throned on ocean's wave. It breaths over the world:

Yet both so passing strange and wonderful!"

(28)

this is, of course countermanded with a destructive view;

The One remains, the many change and pass:

Heaven's light forever shines, Earth's shadows fly;

Life, like a dome of many-coloured glass,

Stains the white radiance of Eternity,

Until Death tramples it to fragments.

(29)

Cartoonists used Death in just the same way, cynically. 140 warns against excesses of the flesh, war utilises Death in the French Revolution (141) and in 142 Death thanks Chancellor Bismark for all the wars he created. Death is also shown in a lighter way, Richard Dagley's, Death's Doings, (143) shows Death playing cricket with Chance and Time (a fair analogy for life), along with poetry, and a serious message about the unpredictability of life. The misconceptions continue, a 'Book of the Dead' is mistakenly called 'The English Dance of Death' (144), though this is an interesting image for the objects at Death's feet, objects of modern destruction, and for the bats at the top, darkness and Death.

Medieval images are re-used, 145 is based on Dante's Divine Comedy, complete with two capering corpses/skeletons who look down on the scene with glee, and a Jesus-like figure lurking in the background. 146 is a darker image, J. F. Millet's sombre rendering of Death and the Woodcutter, again a fleshy Death, complete with scythe who nonchalantly relieves a man of the burden of life. Death wears sackcloth rather than impressive black robes, in-keeping with a time that ironically never dressed Death in such a fashion. Edgar Allen Poe uses a medieval setting for 'The Masque of the Red Death,' where a stately Death brings the plague to arrogant aristocrats who try to hide from the deadly plague, the Red Death, by hiding in a castle. It contains several references to death including the stopping of the clock, the extinguishing of the eternal flame suggests that for their arrogance they will not find eternal rest in paradise,

"The figure was tall and gaunt, and shrouded from head to foot in the

habiliments of the grave. The mask...was made so nearly to resemble

the countenance of a stiffened corpse...And now was acknowledged the presence of the Red Death. He had come like a thief in the night. And one by one dropped the revellers in the blood-bedewed halls of their revel, and died each in the despairing posture of his fall. And the life of the ebony clock went out with that of the last of the gay. And the flames of the tripod expired. And Darkness and Decay and the Red Death held illimitable dominion over all."

(30)

Charles Dickens also used Death in 'A Christmas Carol,' showing Scrooge his grave, (147) a Death that is more darkness than substance, the presence of death rather than the actuality;

"It was shrouded in a deep black garment, which concealed its head, its face, its form, and left nothing of it visible save one outstretched hand. But for this it would have been difficult to detach its figure from the night, and separate it from the darkness by which it was surrounded."

(31)

The apocalypse yet again provides inspiration, with little new to say on the subject (148), again Death is partially fleshed, William Blake's version fully so (149). However, the best must be the moody interpretation from Turner, (150) where a skeletal Death can be seen slumped over his horse, his job done, Death is then defeated himself.

Sex is resurrected for the new century with Redon's 'Death; my irony surpasses all others.' (151) A female torso is pulled out of a void to create a Death of darkness, a femme fatale quite literally. With a skulled visage that appears from under the sensually flowing hair complete with cut roses, the void vagina-like giving birth to a creature of enigma, the ultimate Death.

1900- The Resurrection and Commercialisation of Death

All things they have in common being so poor,

And their one fear, Death's shadow at the door.

(32)

There was little use of Death in funerary after 1900, after the Victorian age destroyed Death in this area. There is now a strong taboo against using strong images on funerary, the previous monuments are now considered distasteful for modern funerary purposes."The richness of funerary architecture is undeniable. It is all the more depressing to contemplate contemporary funerary design. The uninspired tombstones or memorials erected today have added new terrors to death."(33) This is balanced by the vast usage of 'The Grim Reaper' in film, with Death also being used in artistic and written work (32). Most of the stronger paintings, prints and so on come from the first half of the twentieth century, with artists such as

Salvador Dali, George Grosz. After 1960, Death is seen less and less, apart from satirical cartoons, horror movies, and later, adorning heavy metal band record sleeves.

The World Wars created vivid uses of Death, in both new and old ways. George Grosz created dark images of war that told the truth about the situation faced by the men, with bodies, rats, filth. In 153 the soldiers are stalked by Death, who hides in the back of the painting, knife in hand. He wrote of the painting, "My present oils are truly German maybe romantic where Death, a very medieval Death, appears" (34).

The First World War had a bloody impact on the world, and it's citizens, it was vowed that it would 'never happen again'. However, it did. From these two different wars poets often created some of the more memorable impressions of war. Some died, Wilfred Owen (35) for example, the poetry all the more meaningful because of it. However the poetry wasn't always bitter, referring to Death as both a friend and comrade, as well as an enemy (35 and 36). 37 and 38 reveal much of the pessimistic mood of between the wars.

Oh, Death was never an enemy of ours!

We laughed at him, we leagued with him, old chum.

No soldier's paid to kick against His powers.

(35)

Soldiers are citizens of death's grey land,

Drawing no dividend from time's tomorrows.

(36)

All has been looted, betrayed, sold; black death's wing flashed ahead.

(37)

He knows death to the bone-

Man has created death.

(38)

As the world recovered after the first, only a few foresaw the second, this cartoon of 1933 is a chilling prediction of the holocaust to come (154). Here Hitler is revealed to be little more than a disguise, underneath lurks the bony visage of Death as he commands his skeletal followers, and swings the swastika-styled scythe dripping with blood, darkness closes in around them.

At the beginning of the Second World War Dali created the 'Visage of War,' (155 and 152, chapter title page) a haunting, imaginative use of the standard skull. 155 contains a full battle scene on the top of the skull, but it is 152 that captures the unrelenting horror of war with withered, mummified skulls that scream at the viewer, each orifice filled with another skull, their orifices filled with skulls, giving the impression of never ending agony as they curve off into infinity. The head "Stuffed with infinite death" (39), is an allegorical piece not only about war, but the horrors endured in the Concentration camps, and the mass murder of the prisoners. Paul Klee (156) uses the skull in a slightly different way, the word 'Tod' (German for death) manipulated into the features of Death. Everything in the picture is linked, echoing unity in death, similar in principle to 'Dance Macabre,' everyone is equal.

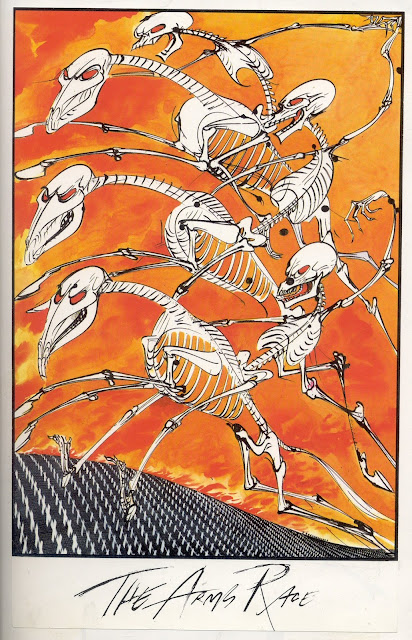

When the first ever atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, it would mark the beginning of the atomic age, and the protests against its use. Grosz now started to populate his own world with skeletal figures, a nightmarish world where people were "utterly without hope, without any meaning." (40) 157 illustrates on of these figures, a decayed ageing violinist, his face barely more than a skull, his stomach strangely red, as if he were a fifteenth century illumination of Death, the stomach slit to reveal the inner workings. His eyes are blank holes, the empty eye-sockets of a man without a soul. Gerald Scarfe, the creator of many vivid images, takes up on this in 1983 where Death asks, 'WHO WON?', against the mushroom cloud and blasted landscape of an atomic holocaust (158). President Johnson becomes Death in 159, shackled to the Vietnam War. Scarfe tackles atomic war in 1987 example (160), where three skeletal riders gallop triumphantly over a mass graveyard, and a sky full of flames.

Death is such a recognisable image he is still used in political cartoons, another Scarfe cartoon, 161, The 'Spectre of Unemployment'. Death is also used in humour, 162 an example of satirical comedy using Death to highlight flaws in the English Judicial system. Scarfe again highlights the dangers of motorways in 163 as Death emerges from the twisted wreckage of a car. Other forms of comedy aimed at adults include Gary Larson's 'The Far Side' cartoons, often twisting familiar aphorisms (164).

Death and Sex reached new heights in the twentieth century, 165 is more typical of earlier versions where a nearly naked woman swoons in the arms of Death. Alfred Kubin also took up an ancient tradition when he produced his again misnamed 'Dance of Death' in 1918, with striking results (176), the girl is dead and lying in a coffin, naked, the scene appears voyeuristic, you question Death's motives towards the woman. Sex and violence meld together in another of Kubin's prints (167), a girl has hung her self. Death clings obscenely to the body like a giant insect, his naked body pulling down her dress to expose her breasts, creating a macabre titillation not felt before, creating a striking if horrific new side of Death. Life in the city, especially life that indulged in excesses, including sex gave Grosz a subject for 168. The picture is dominated by two naked 'fantasy' women, the top one with an almost skull-like leer, mirroring the three figures of Death that provide warnings and reminders to the rich.

Dali often twisted the image of Death and sex to intriguing lengths, in for example, 'Atmospheric head of death sodomising a grand piano.'(169) Dali was fascinated by death, and once wrote, "I am friendly with death-after eroticism it's the subject that interests me the most." (41) Scarfe produced the startling image of 'The Grim Raper' (170) a twist on the famous name that again stretches the boundaries set down in earlier times. Not all examples are as blatantly crude as this, Gustav Klimt's erotic nudes with Death from the start of the century only hint at sexual content with the sensuous nude human form (171 and 172). Death peers over the shoulder of a pregnant woman in Hope I (172), contrasting the miracle of life with

the shadow of Death we all live under. Edward Burra's 'John Deth,' (173) captures the indulgent party mood, with all the excesses, and Death. 'Deth' dances with a woman, beside them dance a couple the female appearing to be near death herself with her skull-like visage. Deth lacks the hourglass, but has a scythe and sweeping (red) robes. In the background (174, detail), bats can be seen in the night sky. His name, John Deth is also an interesting choice, such a common name emphasises the universality of death.

Illusionary work plays with Death, 175 is a clever illusion, the woman makes up the skull as she pampers herself. Dali also uses the skull (176) and seen through half-closed eyes, the effects are very real, the viewers subconscious registering the warning before the conscious mind can, an interesting twist to an old theme warning of death.

Perhaps the most vivid usage of Death in recent times occurs in the cinema, a great deal of this imagery coming from America, as its influence bleeds into the far more ancient cultures of the rest of the world. There are exceptions, the most noticeable being Ingmar Bergman's 'The Seventh Seal' (177-178) from Sweden, where Death plays a game of chess for the life of the knight, and cheats. Death is a pale corpse-like figure, complete with robes and scythe. The origin of Death playing chess comes, in this example, from Berman's childhood listening to his father preach, and staring at 'medieval paintings' on the walls, one of these being Death playing chess with the crusader, along with several other scenes he used in the film, including Death hacking down the tree of life to reach Skat, an actor. (42)

American examples include, Roger Corman's 'Masque of the Red Death,' an adaptation of the Edger Allen Poe tale, 'Bill and Ted's Bogus Journey', where a familiar looking Death rather loses his dignity in with smelly feet and losing to their choice of games (179-181) (which includes Battleships (179) and Twister (180) among others). Another use of Bergman's Death is in 'The Last Action Hero', where he comes to life from the film (182-183). A more skeletal Death also appears in a film about AIDS, the participants of the Gay Halloween Parade turning into skeletal beings, a sort of mix between Dance Macabre and a Dance of Death (184), with the Grim Reaper himself joining in (185).

A Death-like figure is the star of 'The Nightmare Before Christmas,' (186) a stop-animation children's film linked again to Halloween, which is a very American tradition that seeps into films (187). Skulls are used to illustrate the content of a film, i.e. horror (188-189). The Grim Reaper is even the basis for a new foe for Batman, (the animated version) in the new movie 'Mask of the Phantasm.' (190) The underlying character is female, probably to create 'shock' value when the identity is revealed. Death even appears on television, as a judge for Homer Simpson as the Devil battles for his soul (191), or in a skeletal form for the credits for a documentary on death (192-193) or as a children's cartoon (194). Death still continues to appear and appeal to modern audiences.

Horror often uses both the skull and Death to illustrate covers of books. 195-198 shows varied examples of use, from half skull, half flesh, to illusion pieces and children's books(195). Authors who have used Death as a character includes Clive Barker, Terry Brooks (195) Stephen King (196), Neil Gaiman, who uses a female Death who looks very much alive (197), and Terry Pratchett (198-200). Pratchetts books are particularly interesting as Death is quite a mild character and has starred in many of his 'Discworld' books (198) vaguely trying to understand the intricacies of the human race, or what he can learn from the last few moments of a persons life. Of course, he is 'only doing his job'.

Death is used to decorate endless amounts of objects, and indeed becomes some of them, such as 199 and 200, based on Pratchetts Discworld. 201-207 has other commercially available products, from Halloween masks and toys, skeleton warrior toys, complete with an arsenal of weapons (including scythes), this one is, incidentally female (203). Even everyday items such as watches and key rings are decorated (204-205), many even glow in the dark, such as the three examples on 206. 207 is a five foot skeleton, again used for Halloween. The Grim Reaper is used on a Ghost Train on Bridlington front (208-209), another example of how blasé our civilisation can be about a subject that is so rarely spoken of candidly.

The Alchemy Charter (210-215), is a company that makes varied objects and often keeps to the original spirit of Death producing pieces as varied as belt buckles to tattoos (209 and 210). 211 has among other things, buttons made as skulls, necklaces with pendants such as 'The Angel of Death' and Death's heads with both leathery and feathered wings (212). Also rings with the Grim Reaper on, and a dead hand holding a living one in 'The Pact' (213). Even sand timers and their successors, clocks, are adorned with Death. These can be related back to objects and ideas from the past.

Death and skulls are used also for logo's in and out the horror industry, album covers and even a comedy thriller on the radio uses the skull or full figure to advertise or emphasise the product (216-218). On an album cover Cher makes herself into an Angel and Death, complete with wings and skull, again Death is down (219). Death also has a brand of cigarettes (220-221), and his face covers the box with subtle inclusions such as the crest including a coffin and the phrase 'Et in Arcadia Ego.' leaving no doubt of the risks of a product that '...kills people when used exactly as intended' (43). Despite all of his, Death occurs most often in literature and common speech as a cliché. (222) (44-47)

"...the Grim Reaper gets us all, one time or another, sooner or later."

(44)

'Sleep was like a brief death. Death was black.'

(45)

"It was Death personified, the Grim Reaper without his voluminous black robes and scythe, on his way to a masquerade ball in a costume of flesh so thin and cheap that it was not for a moment convincing."

(46)

"I? KILL? Said Death, obviously offended. CERTAINLY NOT. PEOPLE GET KILLED, BUT THAT'S THEIR BUSINESS. I JUST TAKE OVER FROM THEN ON. AFTER ALL, IT'D BE A BLOODY STUPID WORLD IF PEOPLE GOT KILLED WITHOUT DYING, WOULDN'T IT?

(47)

GRIM REAPER.

We started with the noble Death, imaginative, gleefully going about his work, a fear-inspiring cadaver not alone in his quest, joined by hundreds of other 'Death's.' He ended up being a poor shadow of his former self. The skeletal figure no longer scares a gore-hungry public, Death has now lost his nobility to become an object of ridicule and amusement (i and ii), with few moments that re-capture the spirit of the past.

I have noticed this steady shift through out this dissertation, the gradual wearing down of the power of such images as Death and Heaven, Hell. In currant times the horrors of 'modern living' rob the medieval beliefs of their power. After all, Heaven can be reached by drugs, cancer and AIDS have replaced the plague, we can no longer hide behind ignorance of the causes of these diseases, or put our faith in God totally to save us as medicine finds new ways to track the progress of our death. The prospect of Hell on Earth is not farfetched with the threat of nuclear holocaust, one still valid as long as Russia remains in turmoil, and megalomaniacs can reach positions of power.

However lack of belief doesn't always stem from negative sources, lack of ignorance means that the drugs can be used to save lives, or extend, pain free, others. It could be said that the lives lost at Nagasaki and Hiroshima had a positive aspect, without that limited experience of nuclear holocaust, man could have wiped himself out a generation ago. The general 'loss' of the negative influences of the past seem insignificant to what can replace them, positive, or negative.

So shalt feed on Death, that feeds on men,

And Death once dead, there's no dying then.

(43)

Of comfort no man speak:

Let's talk of graves, of worms, and epitaphs;

Make dust our paper, and with rainy eyes

Write sorrow on the bosom of the earth.

Let's choose executors and talk of wills.

(44)

Photograph and Illustration Credits

Frontispiece

Top/ Extracts from the Dance of Death Alphabet. Designed by Hans Holbien the Younger, and engraved on wood by Hans Lutzelburger, Basle, 1528....(82)

Bottom/ Detail of a cross leaning against the church of Neiderwiltz, Luxembourg, 17th c....(56)

Intoduction; Death.

i/ Various Tarot cards from about c.1400-c.1900....(99 and 100)

Before c.1400

Chapter title page/ 1/ Mosiac, Termi Museum, Rome....(56)

2/ Ceiling Boss, the Four Horsemen, Norwich Cathedral, 1340-1410....(33)

3/ Ceiling Boss, Death followed by Hell, Norwich Cathedral, 1340-1410....(33)

4/ Illustration from Boccaccio's Decameron, 14th c....(56)

5/ Three Living and Three Dead, Lisle Psalter, English manuscript, early 14th c....(40)

6/ Recumbent figure, Saint Vaast, Arras 14th c....(56)

7/ Poison bottle label by an unknown Rhenish artist, 1480-90....(82)

8/ The Vanity of All Earthly Things, Hans Baldung, 15th c.....(44) (Bosch, part 32, 1990)

9/ Death and Pride, Raunds Church, 1420....Photograph, The Author

10/ La Grande Dance Macabre des Homme,s Guyot Marchant and La Grande Dance Macabre des Femmes, Antoine Verard, Paris, 1486....(11)

11/ Illumination featuring Death, 15th c.....(99)

12/ Ghibertis Bapistry doors, Florence, 1402....(99

13/ Illumination For Mary of Burgendy's Book of the Dead, 1482....(40)

14/ Danse Macabre, la Chaise-Dieu,15th c....(40)

15/ )Danse Macabre, la Chaise-Dieu,15th c....(40)

16/ Dance Macabre fresco, Meslay.le. Grant, Eure.et.Loir, 15th c....(56)

17/ Dance Macabre fresco, Meslay.le. Grant, Eure.et.Loir, 15th c....(56)

18/ 'La Grande Dance Macabre', Lyons, 1499....(40)

19/ Allegorical Fresco depicting the Black Death, 14th c....(60)

20/ Death and the Miser, Heironymous Bosch, 1485-90....(11)

21/ The Four Horsemen, Albrecht Durer, 1498....(44) (Durer, part 26, 1990)

22/ The Four Apocalyptic Horsemen, Bartholomaus von Uncle, from the Cologne Bible, 1479....(82)

23/ Detail of The Last Judgment, Hubert Van Eyck, c.1426....(11)

24/ The Army of Death, 15th c.....(9)

25/ The Triumph of Death, Palerma, 15th c....(96)

26/ The Triumph of Death, Florentine School, 15th c....(53)

27/ Orchestra of the Dead, Liber Cronicarum, Nurenburg 1493....(99)

28/ Three Living and Three Dead fresco, 15th c....(11)

29/ Three Living and Three Dead, fresco, Raunds, 1420....Photograph, The Author

30/ Three Living and Three Dead (detail of Dead), fresco, Raunds, 1420....Photograph, The Author

31/ Three Living and Three Dead (detail of Living), fresco, Raunds, 1420....Photograph, The Author

32/ Bishop Richard Fleming, Lincoln Cathedral 1431....Photograph, The Author

33/ Bishop Richard Fleming (detail), Lincoln Cathedral 1431....Photograph, The Author

34/ Momento Mori, Jacob Bellini, 15th c....(57)

35/ The Holy Trinity, Masaccio, 1427....(44) (Masaccio, part 45, 1990)

36/ Illumination featuring Death and God. Miroir de l'humaine salvation, Vincentde Beauvais, 15th c....(56)

1500-1599

Chapter title page/ 37/ The Tor Abbey Jewel, c. 1546....(3)

38/ Delivering an Anatomy Lecture, John Banister, 16th c....(29)

39/ De humani corporis fabrica, Andre Vesale, 1543...(56)

40/ Death with an Hourglass, Strasbourg School, 16th c....(56)

41/ Preaching Skeleton, Velez Chapel Cathedral of Murcia, Spain, 16th c....(56)

42/ The Plauge, Paris, late 16th c....(56)

43/ The Foljambe monument, Chesterfield, 1558....Photograph, The Author

44/ The Foljambe monument, detail....Photograph, The Author

45/ The Foljambe monument, detail....Photograph, The Author

46/ The Foljambe monument, detail....Photograph, The Author

47/ Shroud brass of Rev. Ralph Hamsterley, Oddington Oxon, c.1510-1515....Photograph, The Author

48/ Sir Roger Rockley, St Mary's church, Worsbrough, 1533....Photograph, The Author

49/ Sir Roger Rockley, detail of cadavar....Photograph, The Author

50/ Medieval Wheel of Life, woodcut, 1558....(11)

51/ The Knight, Death and the Devil, Albrecht Durer, 1513....(44) (Durer, part 26, 1990)

52/ Engraving by Augusto Veneziano after a design by Rosso Fiorentino, Bibliotheque National, Paris, 1518....(56)

53-58/ The Dance of Death, Hans Holbein the Younger, 1538....(24)

53/ The Expulsion From Paradise.

54/ The Knight.

55/ The Seaman.

56/ The Nun.

57/ The Old Woman.

58/ The Escutcheon of Death.

59/ The Triumph of Death, Pieter Brueghel, 1562....(66)

60/ Death and the Gallant, Newark on Trent, 1520....Photograph, The Author

61/ The Knight, the Woman, and Death, Hans Bauldung Grien, 16th c....(56)

62/ Death and the Young Woman, Nicolas Manuel Deutsch, 1517....(56)

63/ The Young Woman and Death, Hans Bauldung Grien, 16th c....(56)

64/ Entrance to a plauge graveyard,Rouen, France, 1521....(44) (Grunewald, part 37, 1990

65/ )Ambassadors Jean de Dinerville and Georges de Selve, Hans Holbein the Younger, 1533....(44) (Holbein, part 24, 1990)

66/ Ambassadors Jean de Dinerville and Georges de Selve, detail, 'rectified' view of distorted skull....(44) (Holbein, part 24, 1990)

67/ The Burgkmaier Spouses, Lucas Furtenagel, 1529....(56)

68/ Dr John Bull, 1589....(29)

69/ The Judd Marriage, 1560....(3)

70/ Printers mark, Andres Gesner, Zuerich, 1550....(97)

1600-1699.

Chapter title page/ 71/ Detail of a cross leaning against the church of Neiderwiltz, Luxembourg, 17th c....(56)

72/ Thomas Mangy, mourning spoon, 1670-71....(3)

73/ St Olave's Church entrance, London, 1658....(89)

74/ Detail from a monument in York Minster, 1620....Photograph, The Author....(91)

75/ Detail from a monument in York Minster, 1615.....Photograph, The Author....(91)

76/ Sir Henry Griffith, Burton Agnes (E. Yorks), 1645....Photograph, The Author

77/ Sir Henry Griffith (detail)....Photograph, The Author

78/ Detail from a memorial, Spelsbury (Oxon), 1640....Photograph, The Author

79/ Winged Skull on a funerary relief, 1609....(56)

80/ Sir Arther and Baroness Heselridge, Nosley (Liecs), 1661....(33)

81/ John Rudhall, Ross-on-Wye detail of a shrouded baby, 1636....(33)

82/ Painted memorial, Worsbourough, 1684....Photograph, The Author

83/ Thomas Isham, Hillesden (Berks)....(33)

84/ Floor slab memorial, 1624....(56)

85/ Winged skull on funery relief, 1609....(56)

86/ Open coffin on tomb, Marville Meuse, 17th c....(56)

87/ Sir John Hotam, South Dalton (Yorks), 1689....Photograph, The Author

88/ Sir John Hotam, detail of skeleton....Photograph, The Author

89/ Edward Pierce, monument to Lady Warburton, 1693....(96)

90/ Lady Abigail Stawell (detail), Hartley Wespall, (Hants), 1692....(33)

91/ Tomb of Alexandro Valtrino, 17th. c....(56)

92/ Sir Henry Lee, detail of canopy with Time and Death, Spelsbury (Oxon), 1631....Photograph, The Author

93/ Tomb of Pope Alexander VII, St Peter's, Rome, 1671-1678....(16)

94/ Players Surprised by Death, late 17th c....(56)

95/ The deadly demon of tobacco "drinking," from an anti-smoking leaflet by Jacob Balde, 1658....(82)

96/ Thomas de Keyser, Doctor Sebastian Egbertsz's Anatomy Lesson, 1619....(56)

97/ The "Theatrum Anatomicum" of the University of Leyden with a Crowd of Curious Spectators, Bartolomeus Dolendo, 1610....(56)

98/ The Mirror of Life and Death, 17th c....(56)

99/ Queen Elizabeth I, a commemorative portrait, c.1608....(29)

100/ John Evelyn, Robert Walker, 1648....(3)

101/ Vanity, after Phillippe de Champaigne, 17th c....(56)

102/ Undertakers advert from c.1680....(33)

1700-1799.

Chapter title page/ 103/ Satan, Sin and Death, William Hogarth, Mid-1730s....(51)

104/ Monument to Lady Elizabeth Nightingale, Louis Francois Roubiliac, Westminster Abbey London, 1761....(88)

105/ Monument to Lady Elizabeth Nightingale, Louis Francois Roubiliac, Westminster Abbey London, 1761....(75)

106/ The Bad Man at the Hour of his Death, after Francis Hayman, 1783....(3)

107/ Sir Brian Tuke, Hans Holbien the younger, 18th c....(3)

108/ Winged skeletal figure carrying medallian, 18th c....(56)

109/ The Old Man and Death, Joseph Wright of Derby, 1773....(44) (Wright of Derby, part 65, 1991)

110/ Jusqu'a la Mort, Francisco Goya y Lucientes, 1796....(5)

111/ Funery medallian of Thomas de Marchant et d-Ansembourg and his wife, Anne Marie Neufonge, Church of Tuntange, Luxembourg, 1734....(56)

112/ Capuchin chapel, Santa Maria della Concezione, Rome, .18th c....(56)

113/ Death giving George Taylor a Cross-buttock, William Hogath, 1758-59....(3)

114/ George Taylor breaks the ribs of Death, William Hogath, 1758-59....(4)

115/ Death being trampled by an Angel, James Dutton, Sherborne (Glos), 1791....Photograph, The Author

116/ Death being trampled by an Angel, detail....Photograph, The Author

117/ The Risen Christ trampling Death, Thomas Freke, 1769....Photograph, The Author

118/ The Risen Christ trampling Death, detail....Photograph, The Author

119/ Monument to General William Hargrave, Louis Francois Roubiliac, Westminster Abbey London, 1757....(88)

120/ Monument to General William Hargrave, Louis Francois Roubiliac, Westminster Abbey London, 1757....(88)

121/ From Nouveau recueil d'osteologie, Jaques Gamelin, 1779....(56)

122/ Death on a Pale Horse, Joseph Hayesnes after John Hamilton Mortimer, 1784....(7)

123/ Engraved slate headstone, Susanna Symons, St James, St Kew, Cornwall, 1729....(3)

124/ Leathery winged skull, Robert Cressant (detail), Cound, Salop, 1728....(33)

125/ Feathered and leathery winged skull Anne Bridell, Lutterworth, 1725....Photograph, The Author

126/ Momento mori of ebony and ivory, 18th c....(56)

127/ 'Snuff Box', shaped like a coffin with hourglass motif, 1792....(3)

128/ Masonic symbol, 18th c...(42)

129/ Masonic symbol, 18th c...(42)

130/ Funerary invitation, 1702....(36)

131/ Funerary invitation, 1705....(3)

132/ Funerary invitation, 1712....(36)

133/ Funerary invitation, Kendall of London, 1720....(36)

134/ Funerary invitation, 1725....(36)

135/ Funerary invitation, A.N. Copywell, c.1740....(36)

136/ Funerary invitation, 1750....(36)

137/ Pressages of the Millennium, James Gillray, 1795....(7)

1800-1899.

Chapter title page/ 138/ Engraving of Death, 19th c....(97)

139/ The Dying Man Prepared to Meet God (mass production), 19th c....(56)

140/ A Grave Idea; An Apartment for a Single Gentleman, T.Jones, 1828....(33)

141/ Death on the barricades in the March Revolution, from a Dance Macabre series by Alfred Rethel, 1848....(82)

142/.Death thanks Chancellor Bismark for the wars he has caused, Honore Daumier, 1845....(44) (Grosz, part 92, 1991)

143/.The Cricketer, from Death's Doings, Richard Dagley, 1827....(3)

144/.Death Seated on the Globe, frontisepeice to The English Dance of Death, Thomas Rowlandson, 1816....(3)

145/.The Comedy of Death, Rodolphe Bresdin, 19th c....(44) (Redon, part 82, 1991)

146/.Death and the Woodcutter, Jean Francios Millet, 1859....(69)

147/.The Last of the Spirits, John Leech. The first Illustration for Charles Dickens' 'A Christmas Carol,' 1833....(17)

148/ Death on a Pale Horse, Benjamin West, 1817....(7)

149/ Death on a Pale Horse, William Blake, 1800....(42)

150/ Skeleton Falling off a Horse, Joseph Turner, c.1830....(104)

151/ 'Death: my irony surpasses all others,' Odilon Redon, 1889....(56) (Redon, part 82, 1991)

1900-

Chapter title page/ 152/ The Visage of War, Salvador Dali, 1940....(61)

153/ The Ambassador of Goodwill, George Grosz, 1943....(44) (Grosz, part 92, 1991)

154/ Cartoon about Hitler from America, Georges, 1933....(44) (Klee, part 89, 1991)

155/ The Visage of War, study, Salvador Dali, c.1940....(23)

156/ Death and Fire, Paul Klee, 1940....(44) (Klee, part 89, 1991)

157/ The Phantom Violinist, George Grosz, c.1947....(44) (Grosz, part 92, 1991)

158/ Who Won?, Nuclear War, Gerald Scarfe, March 13th 1983....(87)

159/ President Johnson is forced from the Presidential race by inflation, the wealfare program, violence and crime and, above all, by the decisive Vietnam Warat the end of his Era. Richard Nixon eventually becomes President, Gerald Scarfe, December 20th, 1968....(87)

160/ The Arms Race, Gerald Scarfe, 1987....(86)

161/ Nigel Lawson, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, promises tax reform and tax reduction, Gerald Scarfe, December 30th, 1984....(87)

162/ From British Jusitice Belive It or Not!, Paul Mitchell, 1994....(48)

163/ Motorway Madness. There is a series of multiple chrashes on Britain's motorways, Gerald Scarfe, January 12th, 1969....(87)

164/ Unwittingly, Irwin has a brush with Death. Gary Larson 1984....(38)

165/ The Young Girl and Death, Adolf Hering, c.1900....(56)

166/ The Woman, from 'Dance of Death, Alfred Kubin, 1918....(60)

167/ In the Basement, from 'Dance of Death, Alfred Kubin, 1918....(60)

168/ Far in the South, Beautiful Spain, George Grosz, 1919....(44) (Grosz, part 92, 1991)

169/ Atmospheric head of death sodomising a grand piano, Salvador Dali, 1934....(61)

170/ The Grim Raper, Gerald Scarfe, 1987....(86)

171/ Medicine, (now destroyed), Gustav Klimt, c.1903....(45)

172/ Hope I, Gustav Klimt, 1903....(44) (Klimt, part 79, 1991)

173/ John Deth, Edward Burra, 1931....(44) (Burra, part 91, 1991)

174/ John Deth ,detail, Edward Burra, 1931....(44) (Burra, part 91, 1991)

175/ German Postcard, c.1908....(56)

176/ The Skull of Zurban, Salvador Dali, 1940....(22)

177/ Death and the knight at the chess board. Publicity photograph from Ingmar Bergman's The Seventh Seal, 1956....(41 and 6)

178/ Death leads the solemn dance to the grave. Publicity photograph from Ingmar Bergman's The Seventh Seal, 1956....(41 and 6)

179/ Bill and Teds Bogus Journey. Death plays Battleships, taken from video still, photograph by the author, 1991....(3)

180/ Bill and Teds Bogus Journey. Death plays Twister, taken from video still, photograph by the author, 1991....(3)

181/ Bill and Teds Bogus Journey. Death tries to sneak into Heaven in disguise, taken from video still, photograph by the author, 1991....(3)

182/ Last Action Hero. Death emerges from the film 'The Seventh Seal,' taken from video still, photograph by the author, 1993....(5)

183/ Last Action Hero. Death exits the cinema, taken from video still, photograph by the author, 1993....(5)

184/ And the Band Played on. (The Living End) The parade, taken from video still, photograph by the author, 1992....(1)

185/ And the Band Played on. (The Living End) Death, taken from video still, photograph by the author, 1992....(1)

186/ The Nightmare before Christmas, Tim Burton 1993....(94)

187/ And You Thought Your Parents Were Weird, 1991....(2)

188/ Vault of Horror. Video cover....(94)

189/ 976-Evil. Video Cover....(39)

190/ Batman mask of the Phantasam, 1993....(93)

191/ The Simpsons, The Trial, taken from video still, photograph by the author, 1994....(7)

192/ The Simpsons, The Verdict, taken from video still, photograph by the author, 1994....(7)

193/ The Dying Game, Title, 1994....(4)

194/ Funnybones, BBC childrens program, 1994....(106)

195/ Miscellaneous book covers featuring death, various authors, late 20th c..(37, 39, 73, 101 and 110)

196/ Stephen king book covers. Creepshow....(95), Skeleton Crew and The Shining....(37, 73)

197/ Neil Gaiman. Death. the high cost of living. Cover and page taken from book....(25)

198/ Terry Pratchett, book covers from Mort (graphic novelization), Soul Music, The Discworld Companion, Reaper Man....(37, 73, 110)

199/ Death and Binky. Small sculpture by Clarecraft Designs....From the collection of the author, photographed by the author.

200/ Death, the Death of All Rats, the God's Dice Box and a small pewter Death with scythe. Small sculptures by Clarecraft Designs....From the collection of the author, photographed by the author.

201/ Various 'Death' gifts from 'T Shirts' to ornaments, assorted makers and sources....(108, 110)

202/ Halloween toys. Mask, rubberstamp, top of sweet tube, 'grabbing skull,' glasses, badge of a skull, eraser, mock 'ivory' skull, wind up 'chattering skull'....From the collection of the author, photographed by the author.

203/ Skeletal toy (female). From the 'Skeleton Warriors' range by Landmark Entertainment Group....From the collection of the author, photographed by the author.

204/ Halloween objects. Hat, rubber skeleton, keyring, skeleton earrings, pendant, lying skeleton badge and watch....From the collection of the author, photographed by the author.

205/ Halloween objects. Detail....From the collection of the author, photographed by the author.

206/ Halloween objects. Rubber skeleton, lying skeleton badge and watch, all 'glow in the dark'....From the collection of the author, photographed by the author.

207/ Five feet tall skeletal figure....From the collection of the author, photographed by the author.

208/ Ghost train. Bridlington fairground....Photograph, the author.

209/ Ghost train. Detail of 'Death'....Photograph, the author.

210/ Assorted objects from 'The Alchemy Charter'....(1)

211/ Assorted objects from 'The Alchemy Charter,' Skull necklace, skull buttons, Grim Reaper ring, 'The Pact' ring, skeleton key, Death's Head, Angel of Death pendents....From the collection of the author, photographed by the author.